Originally posted on Brookings.

As big cities across the country recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, they are staring down some formidable challenges in their downtown commercial and office districts, as well as in their labor markets. Today, most U.S. downtowns have lower levels of activity compared to before the pandemic, especially in larger cities—and the federal relief that has compensated for lost sales taxes, transit fares, and other revenue is running out.

At the same time, what many initially called a “great resignation” in the labor market turned out to be more of a “great reshuffle”—a rapid shift of workers from one job, industry, or career into another as people re-evaluated their living and work arrangements during the pandemic. Both job openings and job quits reached record highs in 2021.

With last week being National Apprenticeship Week, this piece asks: What role can apprenticeships play in solving these challenges and bringing about more inclusive downtown economic development?

The pandemic’s workforce impacts are still challenging downtowns

Downtowns are confronting two challenges that will take collective effort to address.

First, even as the share of workers (and their share of days) working remotely has gradually declined since the onset of the pandemic, office vacancy rates in large downtowns have continued to rise, and at a faster rate than across the overall region. Even if this divergence eventually reaches a new equilibrium, it is opening up a gap in the relationship between downtowns and work.

The second challenge relates to dysfunctional labor markets. The pandemic’s initial economic shock was concentrated in Black and Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods, which saw severe job losses. These jobs have been slow to return and workers have been slow to return to them, as the protracted pandemic led to accelerated retirements and low immigration, while surging consumer demand, lack of child care, and other factors contributed to tight labor markets and high employee turnover. Employers are now finding that the old ways of hiring and retaining workers aren’t working anymore. Even in sectors of the economy that did not experience sharp job losses, these old ways of recruitment and selection are reproducing an opportunity gap, with degree-centric candidate screening leaving many workers and neighborhoods on the sidelines.

By embracing apprenticeships, downtowns are uniquely positioned to create a new competitive advantage and value proposition for themselves as talent engines for the future. And the wave of federal funding earmarked for workforce development, infrastructure, innovation, and climate adaptation will create additional opportunities to strategically engage local talent in the reinvention of downtown neighborhoods.

Apprenticeships are not only for the trades

It is time to rethink how we connect local talent to careers and provide more options for people to access high-quality jobs. In the U.S., apprenticeships have a long history of being limited to skilled trade occupations such as electricians, plumbers, and construction workers. These are relatively high-paying jobs, and they remain important for the success of downtowns, particularly as federal infrastructure funding hits the streets.

What is an apprenticeship?

Apprenticeships combine long-term, paid, work-based learning opportunities with structured educational curricula to ensure that the learner gains both education and hands-on experience in a profession of occupation. Apprenticeships are most suitable for jobs that require a mix of hands-on experience and conceptual foundations learned in the classroom. They can be an attractive option for learners who prefer learning by doing, who are seeking paid routes into a profession and/or college degree.

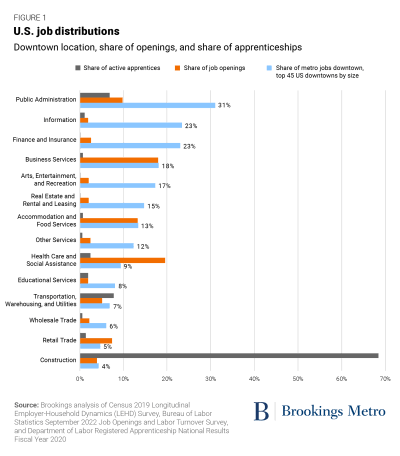

Yet there are many other industries and occupations concentrated in downtowns that are struggling to fill openings and retain workers (see Figure 1). Finance and insurance, professional and business services, and many government administration jobs could benefit greatly from offering apprenticeship pathways from high schools and community colleges into roles that are currently hard to fill, such as project managers, account managers, cybersecurity technicians, and graphic designers.

In Switzerland, apprenticeships are offered across a wider range of industries and professions, and 70% of high school youth participate in them. The most popular choice among apprentices there is the commercial sector, which includes banking, retail, public administration, and some information technology occupations.

Businesses typically benefit from training apprentices as well, although the costs and benefits can vary. Apprenticeships show promise in helping companies become more innovative, build a more diverse workforce, save on hiring and turnover costs, reduce overtime, and recruit and retain workers in jobs that are hard to fill. Researchers Samuel Muehlemann and Stefan C. Wolter found that businesses in Switzerland and Germany were more willing to train apprentices when they could recoup their costs, which was more likely to occur with longer apprenticeship durations, competitive labor markets (apprentices helped reduce hiring and recruitment costs), and/or conversion of apprentices into full-time employees for at least a year.

Barriers to scaling apprenticeships in the US

Overcoming the long-standing pattern of restricting apprenticeships to a handful of skilled trades will require some transformative shifts in our K-12 institutions, postsecondary education, and hiring/career pathways. Although there is bipartisan support for expanding apprenticeships and other earn-and-learn opportunities, most of the efforts to date have come in the form of grant-funded initiatives and pilot programs rather than systems-level changes such as formula funding for apprenticeship intermediaries, redesigning registration processes to suit 21st-century jobs and professions, and creating incentives for states and educational institutions to develop degree apprenticeships or give academic credit for work-based learning.

The top barriers to scaling apprenticeships outside the trades include:

- Low awareness of apprenticeship options among businesses, students, parents, and society has led to a poor understanding of what it is or what its value proposition is outside of a narrow set of industries and occupations where it is normalized.

- State and federal apprenticeship registration processes can be onerous for businesses and may include rules and terms that seem irrelevant for roles outside of the trades (e.g., “journeyman” is gendered and is not commonly used in an office environment).

- Siloed governance structures and funding streams between educational institutions, employer organizations, and learners has made coordination onerous and reduced alignment between available curricula, skills that employers need, and career awareness.

- Misperceptions rooted in the history of apprenticeships and vocational education in the U.S. have contributed to the stigmatization of apprenticeships as a lower-status alternative to a college degree (rather than a paid pathway to a degree). Another common misperception is that apprenticeships require the presence of a labor union.

Despite these barriers, there is growing momentum to expand apprenticeships beyond traditional industries and integrate them into educational systems and degree pathways. These “new collar” apprenticeships (a phrase coined by IBM) focus on professional occupations in industries such as insurance, finance, business, and technology. In Chicago, an employer-led network started by Accenture, Aon, and Zurich North America—the Chicago Apprenticeship Network—brings together employers, education partners, and apprentices to shift hiring practices away from an overreliance on college degrees and supports apprenticeship expansion to cultivate talent from a more diverse range of backgrounds. And in September, New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a historic investment in a new public-private partnership to connect 500 youth to paid apprenticeship roles in finance, technology, and business operations. Technology apprenticeships are also expanding in response to unfilled openings and a need for more racial and gender diversity in technology; San Francisco’s TechSF program was one of the first to expand registered apprenticeships into several information technology occupations.

Watch the recent event | Racial equity and inclusion in tech: Can apprenticeships help change hiring practices?

Such apprenticeship pilots can provide a proof of concept, but real change requires investment in new institutions, pathways, and systems over time. Place-based governance organizations in our downtowns are well positioned to engage local talent that has been kept on the sidelines of economic prosperity, strengthen linkages between education and employment, and expand youth apprenticeships as an opportunity multiplier. What is required for the downtowns of the future is not a new program or pilot, but a realignment of existing institutions that makes it easy for both individual employers and workers to participate.

The pandemic accelerated trends in America’s downtowns, workplaces, and labor markets, so in many respects the future is already here. Expanding apprenticeships to strengthen pathways for local talent into hard-to-fill professional jobs will help cities leverage the workforce they already have to foster inclusive innovation and regional growth.